Albedo

Nat Faulkner

13 July–14 September 2024

The sole pleasure is to discover unexpected results at the end of a rigorous analysis.

— Paul Valéry, Notebooks

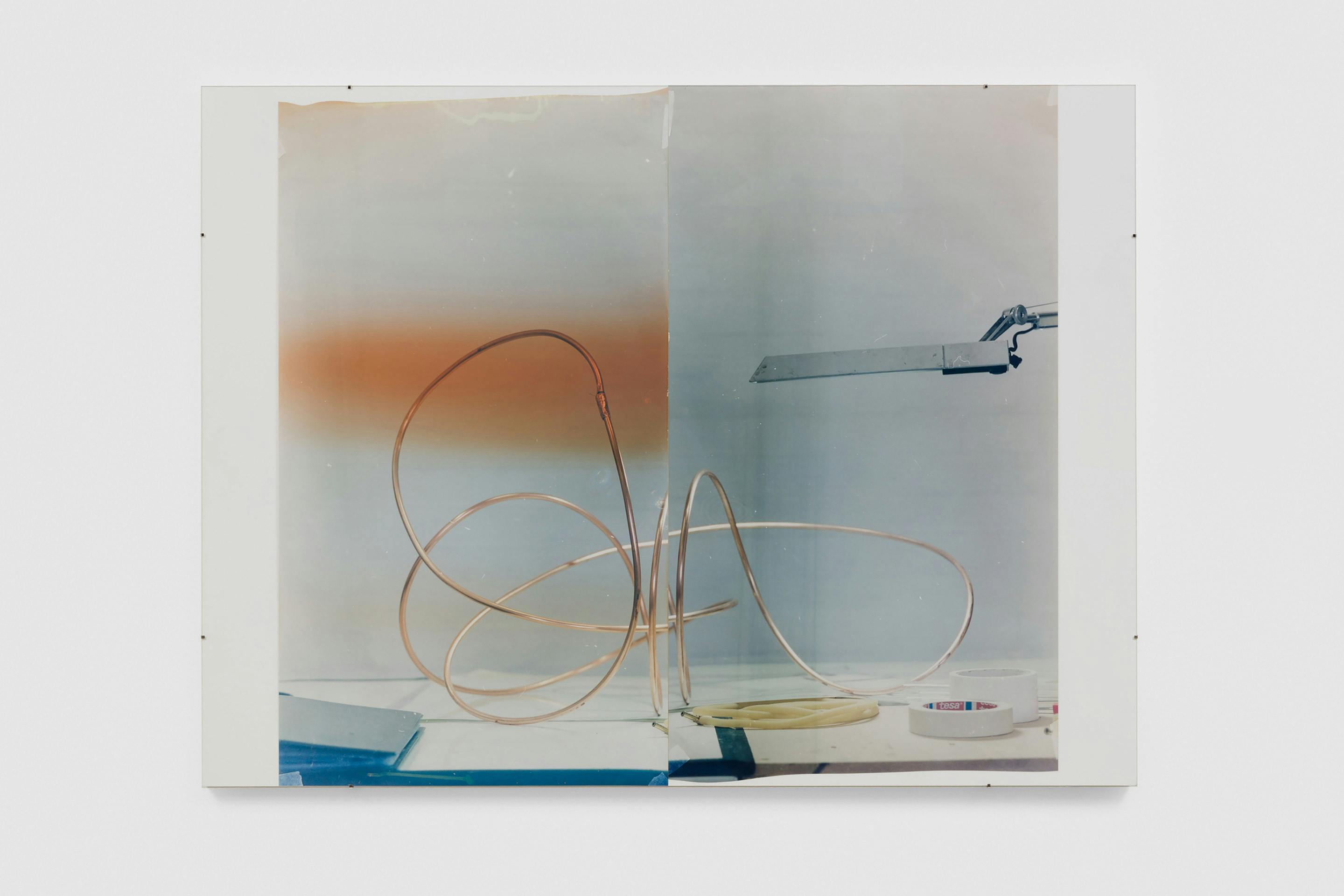

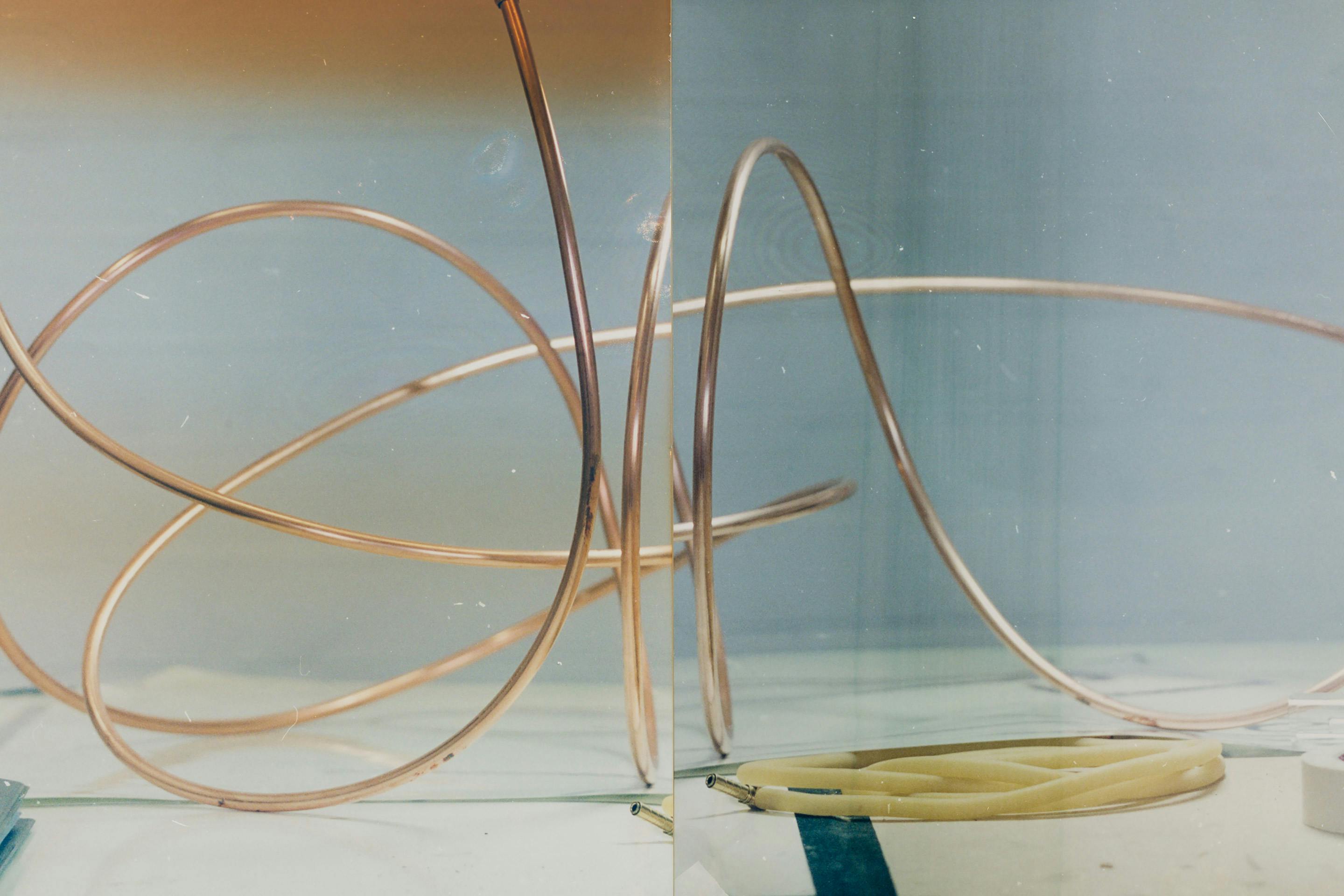

Nat Faulkner wants to know how to materialise an event that is not visible. What would an authentic tool be, he asks, where does the magic come from, what use is our body, and what is the limit of our interventions. Clearly this compulsion to “capture” an invisible event is not so different from the drives and habits of naturalists. In thinking about the aberrations of time and movement, Faulkner invokes the principles of time-lapse photography that Oliver Sacks outlines in Speed and interprets as a way to enhance our perceptions to a degree infinitely beyond what any living process could match. By using instruments of various kinds, he says, we can make up for the limitations of our bodies, and unlock time. Nat Faulkner practises an unsettled but deeply methodical type of photography in order to fashion an elastic perception of time.

In his notes, imbued with stories on altered states, Nat Faulkner exults in the magic of human experience. He is struck by the possibility of manipulating bodily self-consciousness.

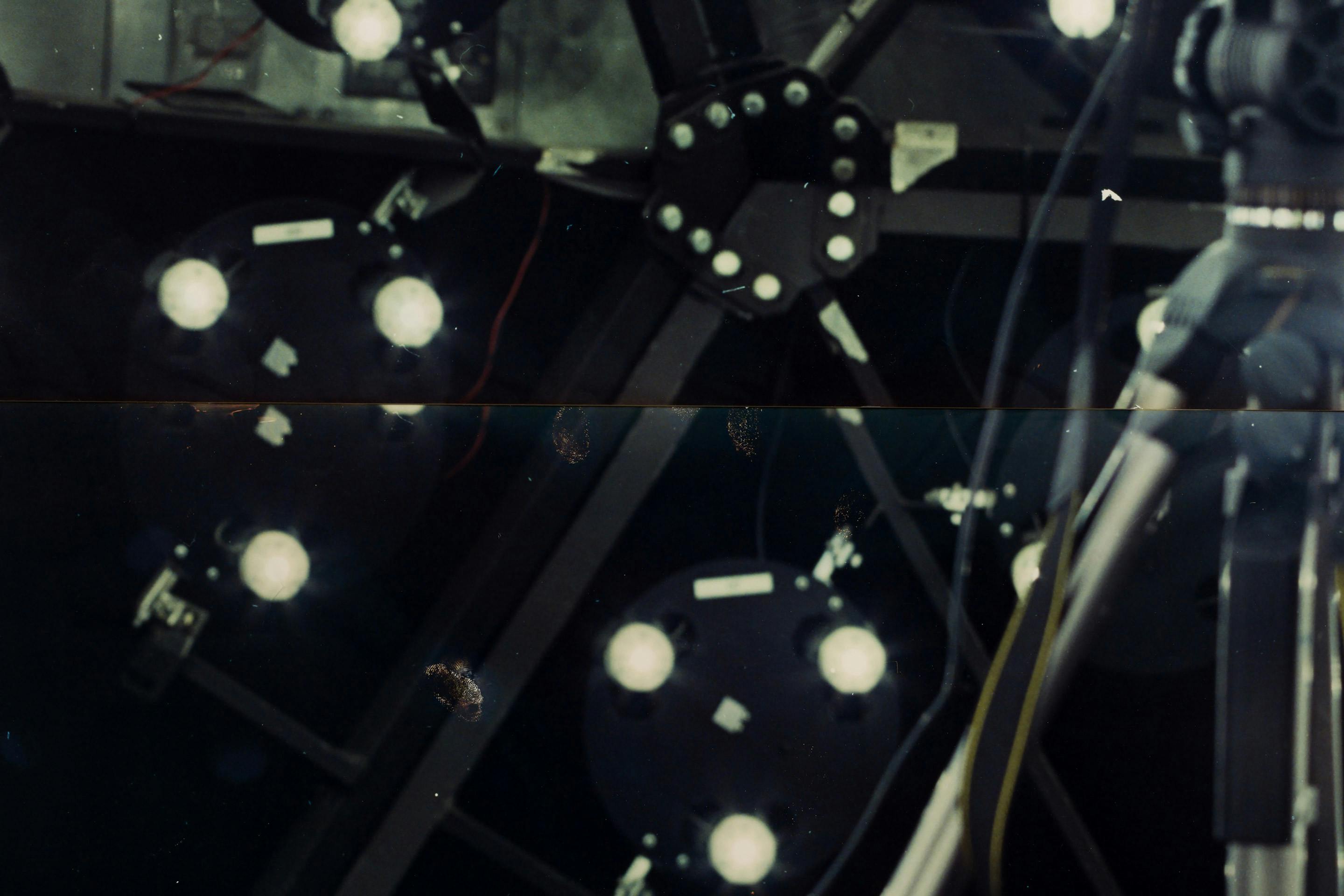

Displacement in time, and the chance of “being disembodied or placed somewhere else mentally,” are contributing factors behind Faulkner’s interest in Dr. Olaf Blanke’s study into out-of-body experiences. There is evidence to suggest that experiential states can be provoked under experimental conditions, and it is not a stretch to imagine that Faulkner, with his installation and glass ampoules, might be attempting to fashion his own comparable conditions, relying, I think it is fair to say, on reflections; the clair de lune to be exact.

One of the ways I came to identify the importance of reflections was via a borrowed painting, a vestige from the artist’s childhood, the portrait of a moon which hangs on the glass wall so we can only read its verso: CLAIR DE LUNE SUR LA POINTE DU RAZ. Faulkner describes this wall as a kind of one-way mirror, which by extension makes us voyeurs; pouring into the chamber is a whole lot of desire. On another occasion it was an ampoule, containing silver, a highly reflective element, and photo developer, which started me thinking about the nature of reflections as well as the “wet processes” of analogue photography and the darkroom, a chamber evocative of the lighting simulator present in Faulkner’s photography.

In his presentation to the École Polytechnique Fédérale in Lausanne, Switzerland, Dr. Blanke uses the image of M.C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere to aid his introduction to “the self” and “out-of-body experiences.” It is widely understood to be not only a reflection of the artist but a reflection of his spirit. Faulkner’s experiment, with the moonlight that reflects into the room along with our desire, might well be considered the heir to Escher’s Sphere. Something about the reflectivity of the moon infuses the reflectivity of our spirits and allows us, in imagination, to “enter all speeds, all time.”

— Written by Robert Frost

Nat Faulkner

(b. 1995, Chippenham, UK. Lives and works in London.) Recent exhibitions include:

Publics, Final Hot Desert, London (2024), Days, Roland Ross, Margate (2024), Deluge, Commonage Projects, London (2022), Bold Tendencies, London (2020), Like a Sieve, Kupfer, London (2020).

Publications

Credits

Images courtesy of Brunette Coleman, London. Photography by Jack Elliot Edwards.